Jeffrey Gibson's U.S. Pavilion at Venice Biennale Took Root in the West

By Chadd Scott on

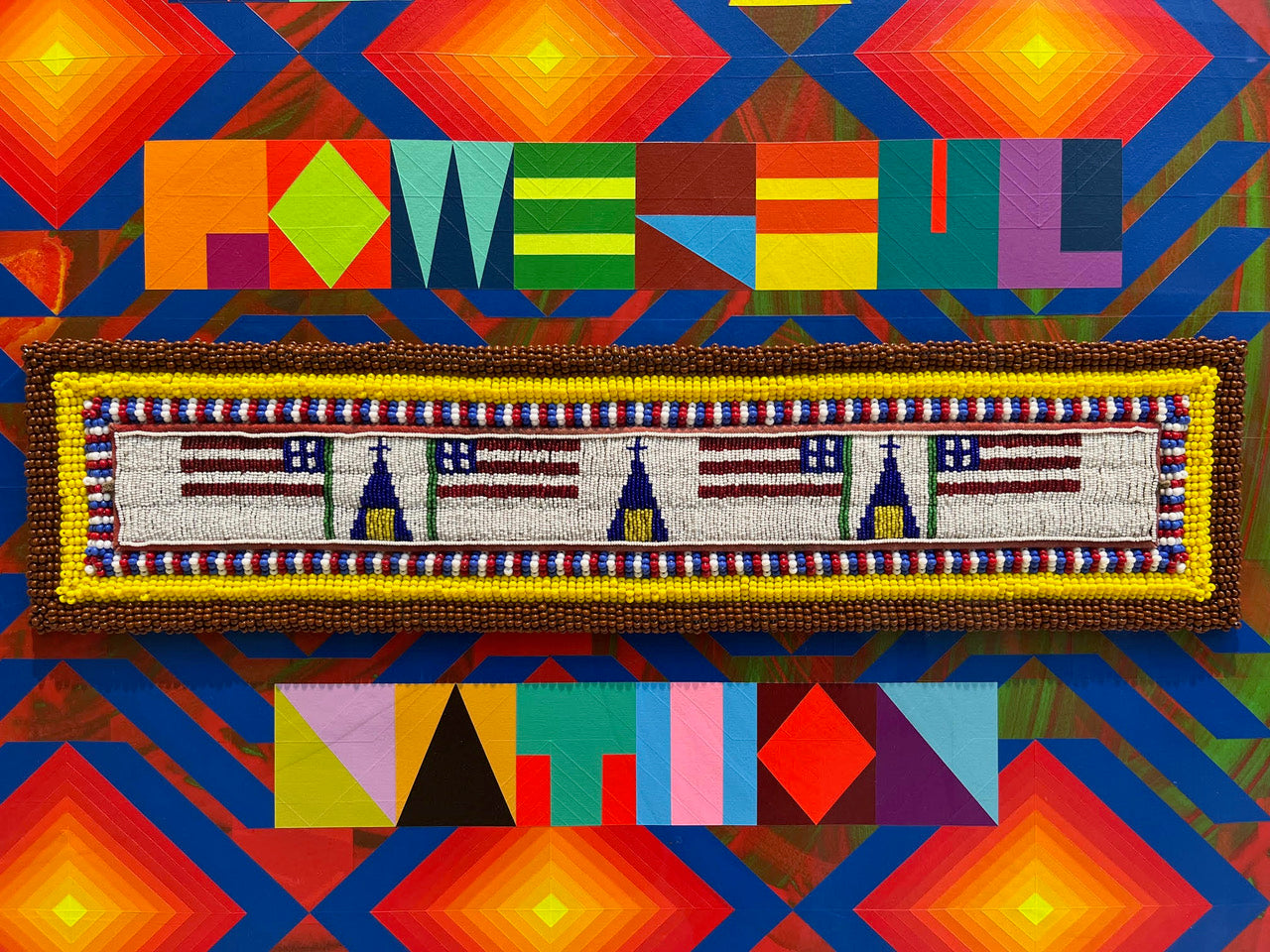

Jeffrey Gibson knows you catch more flies with honey than vinegar. He draws people in with vivid, joyful colors and fantastical geometric designs. Beauty as an entry point.

Then he hits them with colonization’s lasting impact on Native Americans and the country’s endless list of failed promises.

Gibson, (b. 1972), a member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and of Cherokee descent, became the first Native American artist to represent the United States with a solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale – the Olympics of contemporary art – when “the space in which to place me” opened on April 20, 2024.

The title references Oglala Lakota poet Layli Long Soldier’s poem “Ȟe Sápa.” Throughout the show, Gibson incorporates language – in his familiar, you-can-read-it-once-you-see-it script – from foundational American documents including constitutional amendments, legislation, speeches, and official correspondence, as well as song lyrics and musical references.

Gibson wrapped the neoclassical U.S Pavilion in hand-painted murals. Extending across the eastern and western facades of the building are two introductory phrases: the title of the exhibition on the left is joined on the right by “We hold these truths to be self-evident.”

Artwork detail of Jeffrey Gibson painting in 'the space in which to place me' at Venice Biennale 2024 (2)

Other works in the exhibition take on titles like THE RIGHT OF THE PEOPLE TO PEACEABLY ASSEMBLE (2024), and THE RETURNED MALE STUDENT FAR TOO FREQUENTLY GOES BACK TO THE RESERVATION AND FALLS INTO THE OLD CUSTOM OF LETTING HIS HAIR GROW LONG (2024). That painting’s title and its matching text draw from a 1902 letter from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Superintendent of the school district of Round Valley, CA, in which a directive is given for male Indians to cut their hair to “hasten their progress towards civilization.”

A beautiful painting with a sinister foundation.

The exhibition begins in the pavilion’s forecourt with the titular work: a large-scale, site-specific sculpture combing a series of classical sculpture bases in a multi-level platform painted in a singular, vibrant red. Visitors are encouraged to climb the monument, placing themselves atop the platforms, challenging historic notions of who belongs immortalized in public sculpture.

A pair of towering figures welcome visitors inside, The Enforcer (2024) and WE WANT TO BE FREE (2024) stand approximately 10-feet-tall. They take their shape from beads, ribbon, fringe, and tin jingles—elements inspired by traditional Native regalia. Their heads, rendered imperfect and asymmetrical in glazed ceramic, recalling Mississippian effigy pots, an ancient tradition from the American Southeast.

Their bodies bear beaded text on each side: The Enforcer’s chest refers to the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution, known as the “Reconstruction Amendments,” abolishing slavery and intending to protect the civil rights of Black American citizens. Also referenced is the Enforcement Act of 1870 which established penalties for interfering with a person’s right to vote. WE WANT TO BE FREE is emblazoned on the front with additional text from the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, a law granting basic rights to Indigenous people within U.S. boundaries, and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the first federal law to define citizenship and claim all citizens equal under the law.

Installation view of Jeffrey Gibson 'the space in which to place me' at Venice Biennale 2024 (2)

Gibson integrated Native-made objects into the exhibition’s paintings. He sourced examples of traditional Native beadwork – much of it originating in the Columbia River Plateau – including bags, belts, and medallions from websites and estate and garage sales. Applying them first to a felt base and then to painted cotton rag paper, the objects are attached to the surface of the paintings with care and kept intact in their original form. This allows the objects, whose makers are unknown, to be easily removed if a viewer identifies the object and maker.

Should an object be claimed, Gibson has committed to returning the work and commissioning an Indigenous artist to create a replacement or to make one in his studio.

While there are many new works on display, admirers of Gibson will find them familiar, including one of his iconic beaded punching bags.

Visitors to the exhibition are drawn through by a pulsating drumbeat. Its source is the exhibition’s final work, and highlight, a multi-channel video installation, She Never Dances Alone (2020). The video simultaneously honors Gibson’s Native cultural background and club-kid youth.

Originally shown in New York’s Times Square, for this iteration, the video is projected across nine screens and features dancer Sarah Ortegon HighWalking (enrolled Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho) performing the Jingle Dress Dance, a powwow dance originating with the Ojibwe tribe. The centuries-old dance is traditionally performed by women to call upon ancestors for strength, protection, and healing.

Dancing to the beats of First Nations electronic group The Halluci Nation, HighWalking performs in a series of her own dresses adorned with jingles or rows of ziibaaska’iganan (metal cones). As the dance progresses, her image multiplies within each screen and across the gallery, representing generations of Indigenous women and acknowledging their persistence for years to come.

The video puts an exuberant exclamation point on a celebratory exhibition.

Beauty as an act of defiance and resilience in the face of it all.

Installation view of Jeffrey Gibson 'the space in which to place me' at Venice Biennale 2024

Foreigners Everywhere

This Biennale takes as its theme “Foreigners Everywhere,” referencing the global toll of colonization, a global rise in anti-immigration sentiment, and Venice being swamped by tourists among other inspirations. Indigenous responses to colonization fill the national pavilions. Taking the top prizes were a collective of Māori artists and a First Nations artist from Australia.

The main exhibition hall features a powerful presentation about the damage done by U.S. intervention in Puerto Rico. Indigenous artists from Brazil took on their Portuguese colonizers. The Dutch pavilion welcomed a Congolese artist collective who shared that country’s brutal history with colonization through sculptures so rough and tough they prove hard to look at.

Gibson, as a Native American, shares this history, but his approach is 180-degrees in the other direction. He wraps his iron fist in a velvet glove.

Where the world’s other Indigenous artists approached their subjugation and abuse at the hands of European empires through solemnity, agony, and violence – understandably, effectively – Gibson did the same through color, dance, and music.

“I know the joy of being with my family, memories of being with my grandmothers and my aunts and uncles, laughter and food and humor, a place to put down these overbearing traumatic histories and literally just breathe and laugh,” Gibson told me in 2022.

He showed the world that the Indigenous people of what is now considered America are alive and well by throwing a party.

Artwork detail of Jeffrey Gibson painting in 'the space in which to place me' at Venice Biennale 2024.

America’s Artist

Jeffery Gibson isn’t a Western artist, but his selection to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale makes him America’s artist, and that includes the West. The presentation, undeniably, takes root in the West.

Artists and institutions team up when applying for consideration to represent America at the Biennale. Gibson collaborated with the Portland Art Museum and SITE Santa Fe to put on his show.

SITE Santa Fe showed a major exhibition of Gibson’s work in 2022 and the exterior murals for the U.S. Pavilion were produced there. SITE had staff in Venice for two months leading up to the exhibition installing them.

The show was co-curated by Kathleen Ash-Milby, Curator of Native American Art at the Portland Art Museum and a member of the Navajo Nation. Like Gibson, she made history in Venice, becoming the first Native curator to organize a U.S. Pavilion. Like SITE, PAM hosted a Gibson exhibition in 2022 and 2023.

Western institutions have been critical in Gibson’s emergence as one of America’s leading contemporary artists – Native or otherwise. In 2018, the Denver Art Museum presented the artist’s first major museum exhibition and catalogue, vaulting him to another level of prominence.

A level of prominence that has taken him all the way to the Venice Biennale where “the space in which to place me” will be on view through November 24, 2024, at the U.S. Pavilion in the Giardini Della Biennial.